4. First Family (1918-1926)

Robert met seventeen-year-old Nancy Nicholson, in May 1916 when on leave. She was the daughter of the painters William and Mabel Nicholson, sister of the painter Ben Nicholson and herself an artist and an ardent feminist. They were married in St. James’, Piccadilly, on January 23rd 1918, by which time the success of his Fairies and Fusiliers (1917) had established Robert Graves as a poet.

In October 1919 Graves took up his place at St.John’s College, Oxford, where he decided to read English instead of Classics. He rented a small cottage outside the town, in Boar’s Hill, from the poet John Masefield. To supplement their small income, which consisted of Robert’s army pension and the government grant for his university studies, Nancy decided to set up a village shop, but it proved to be a failure. On this and on other occasions the young couple received financial help from their families and also from close friends such as Sassoon, Edward Marsh and T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), who was a Fellow of All Souls’. Graves first met T.E. Lawrence in March 1920, and was to write his biography Lawrence and the Arabs, in 1927; after Lawrence’s death he published their correspondence in T.E.Lawrence to his Biographer Robert Graves (1938). Another companion at Oxford was the poet Edmund Blunden.

In June 1921 Robert and Nancy and their children, Jenny and David, moved from Boar’s Hill, outside Oxford, to the more rural village of Islip. They had two more children, Catherine, born in 1922, and Sam, in 1924. Because of Nancy’s feminist ideas, the two girls were called Nicholson and the boys Graves. Robert, known by the villagers as “The Captain”, enjoyed village life: he joined the football team, supported the local Labour Party and became a member of the parish council for a year. They paid occasional visits to Robert’s parents, who by now had sold the house in Wimbledon and were living in Harlech, and were also in close touch with Nancy’s father, William Nicholson.

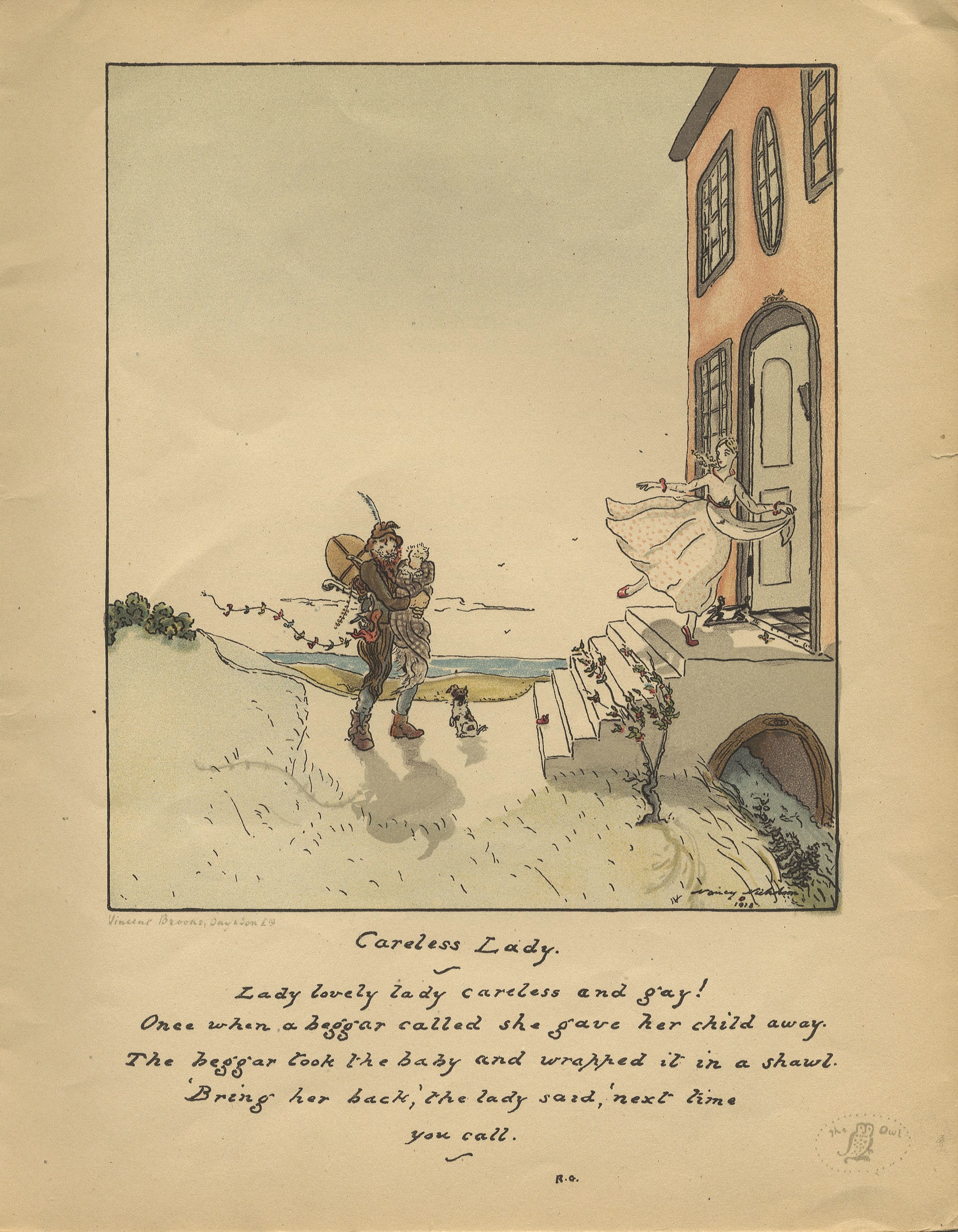

During this time Graves edited, with his father-in-law William Nicholson, a magazine called The Owl, which received contributions from well-known writers, poets and painters of the day. Graves continued to write and publish poetry, but the war-poetry boom was over and Georgian poetry was on the decline; by 1922 he was writing poetry of a psychological and philosophical nature, and this did not reach a wide public. His persistent war-neurosis and his desperate struggle to rebuild his life after the shock of the war were the moving forces behind his poetry of that time. In his university thesis, which appeared in book-form under the title Poetic Unreason, Graves explored the mystery of poetic inspiration, a subject that was to fascinate him all his life and lead eventually to The White Goddess. By the end of 1925 Graves had published eighteen books, including his first attempt at historical fiction, the short novel My Head! My Head!

But Graves found it difficult to earn a living as a writer, and in 1925 he decided to a job as Professor of English Literature in the university of Cairo, in the hope that the trip would also improve Nancy’s heath, who was emotionally exhausted by motherhood and by Robert’s shell-shock.

Help me see you as before

when overwhelmed and dead, almost,

I stumbled to that secret door

which saves the live man from the ghost.

(From “Sullen Moods”, 1921)

St. John’s College, Oxford, was founded in 1554. Graves joined the college in 1919.

“Lawrence’s eyes immediately held me. They were startlingly blue, even by artificial light, and never met the eyes of the person he addressed, but flickered up and down as though making an inventory of clothes and limbs. (Good-bye to All That, chap. XXVIII)

“I worked through frequent interruptions. I could recognize the principal varieties of babies’ screams: hunger, indigestion, wetness, pins, boredom, wanting to be played with; and learned to disregard all but the more important ones.” (Good-bye to All That, chap. XXIX)

His parents house in Harlech, North Wales, where they spent several holidays.

4.6 The Owl: Illustration by Nancy Nicholson of Graves’s “The Careless Lady”.

4.6 The Owl: Illustration by Nancy Nicholson of Graves’s “The Careless Lady”.

The Owl was edited by Graves and his father-in-law, Sir William Nicholson.